AP Syllabus focus:

‘Dependency theory argues that unequal economic relationships can keep poorer regions dependent on, and controlled by, wealthier cores.’

Industrialization and the global economy created long-lasting structural relationships, and dependency theory explains how these relationships generate persistent inequality between wealthier and poorer states.

Dependency Theory: Foundations and Purpose

Dependency theory is a major framework in human geography that examines why economic disparities persist between regions despite decades of globalization and development initiatives.

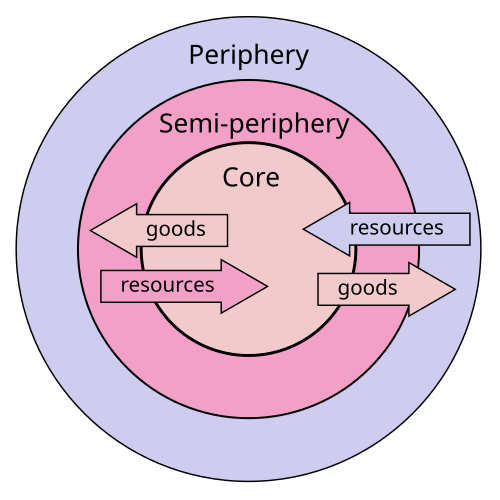

This diagram illustrates the basic logic of dependency theory, showing how economic relationships link wealthier core economies and poorer peripheral economies. It emphasizes that flows of resources, goods, and profits are structured in ways that favor the core. The image includes more detail than required by the syllabus, but all elements support the central idea that unequal economic relationships keep poorer regions dependent on wealthy cores. Source.

Emerging in the mid-20th century, it challenged earlier modernization approaches by arguing that underdevelopment is actively produced, not simply the result of internal shortcomings. The theory’s central idea is that the global economy is structured to benefit core countries while limiting opportunities for periphery countries, creating a cycle of dependence.

Introducing Key Terms

The term underdevelopment is central to this topic, and within dependency theory, it refers to structural conditions created by external forces rather than a natural or original state.

Underdevelopment: A condition in which a country’s economic structure and opportunities are constrained by external control and unequal global relationships.

Dependency theory uses this concept to argue that historical and contemporary ties to wealthier states shape how poorer states develop—or fail to develop—over time.

Economic geographers emphasize that the theory focuses on patterns at multiple scales, from global trade networks to the internal economies of dependent states. These patterns help explain why many countries rich in natural resources still struggle to achieve broad-based economic growth.

Core Concepts and Structures of Dependency

Dependency theory builds on the idea that the world economy functions through relationships of dominance and subordination, often mirroring colonial histories. Wealth flows from poorer regions to richer ones through unequal arrangements that limit local industrialization and capacity building.

The Core–Periphery Relationship

The theory’s central structure is the persistent divide between core and periphery regions, with the semiperiphery acting as an intermediate buffer.

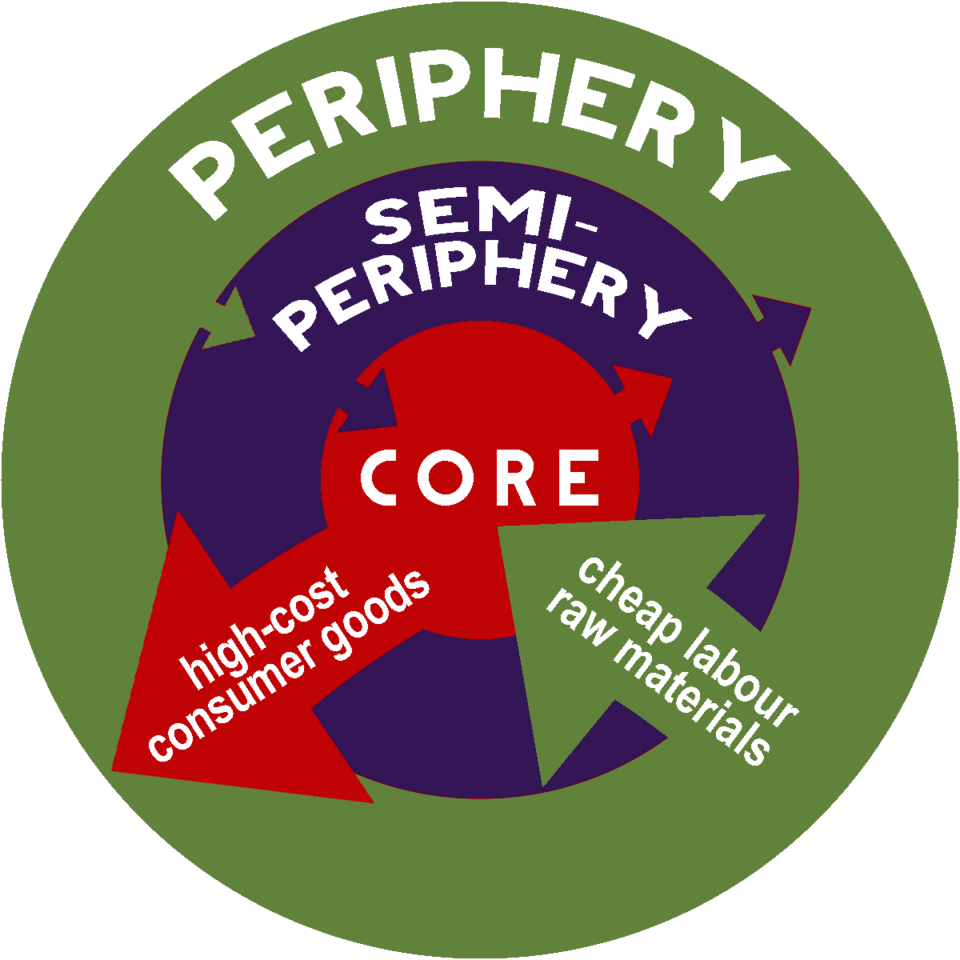

This diagram depicts a core–semiperiphery–periphery structure, highlighting how wealth and power are concentrated in the core while the periphery remains economically dependent. The semiperiphery occupies an intermediate position, linking and mediating between core and periphery. The graphic comes from world-systems theory, which is broader than dependency theory, but it clearly illustrates the hierarchical pattern emphasized in the syllabus. Source.

Core states

Possess diversified, advanced industries

Maintain technological advantages

Exercise political, financial, and cultural influence

Extract profits from global economic relationships

Periphery states

Rely on exporting raw materials or low-value goods

Have limited industrial development

Depend on external financing and technology

Experience capital outflows that prevent local accumulation

Semiperiphery states

Exhibit mixed characteristics

Function as stabilizers in the global system

May exploit the periphery while being subordinate to the core

This global hierarchy supports the reproduction of unequal development patterns, with core regions capturing the most profitable economic activities.

Mechanisms that Produce Dependence

Dependency theory identifies several interconnected processes that maintain inequality across places. These mechanisms reinforce each other and shape long-term development trajectories.

Unequal Trade Relationships

Periphery states often export cheap raw materials and import expensive manufactured goods from core states. This pattern can prevent local industries from becoming competitive.

Low-value exports limit government revenue

High-value imports drain foreign currency reserves

Market volatility exposes producers to unstable global prices

Foreign Ownership and Control

Many industries in periphery countries are owned by foreign corporations, especially in mining, agriculture, and manufacturing. Because profits often leave the country, local reinvestment is limited.

Capital flight: The movement of financial resources out of a country through profit repatriation, investment withdrawal, or currency transfers.

This process reduces long-term opportunities for local development and increases dependence on external investors.

A sentence to maintain spacing before the next block of formal structure.

Debt and Structural Constraints

International lending can deepen dependency when repayment obligations exceed a country’s ability to invest in public services or development.

High interest payments reduce domestic spending

Loan conditions may require policy changes that favor external investors

Long-term debt cycles limit economic sovereignty

Commodity Dependence Connections

Periphery economies often rely heavily on a narrow set of export commodities. This increases vulnerability to global price shifts and prevents diversification, reinforcing dependency theory’s arguments. While commodity dependence is a separate subsubtopic, dependency theory treats such specialization as a symptom of unequal global structures.

Spatial Consequences of Dependency

Dependency relationships produce clear spatial patterns that shape how regions develop economically and socially.

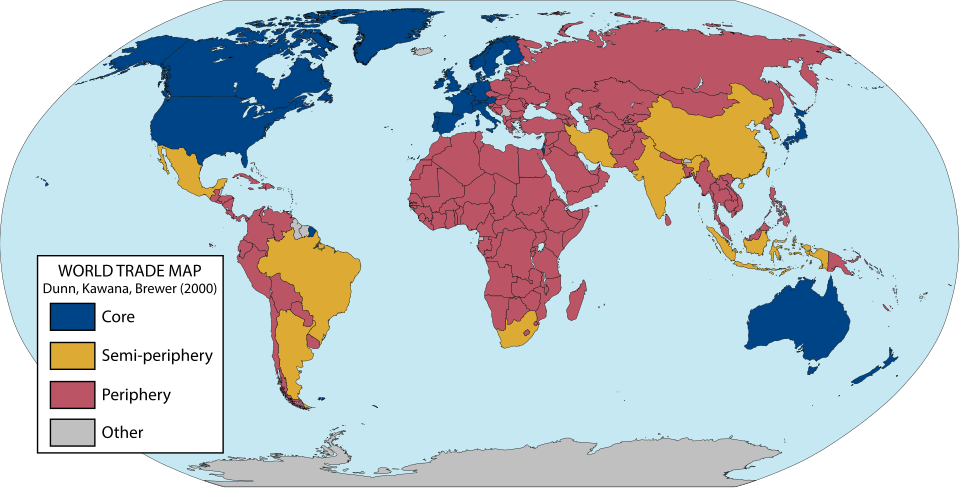

This world map classifies countries into core, semi-periphery, and periphery based on trade and development characteristics. Darker or more prominent areas represent core states with concentrated economic power, while lighter regions show semi-peripheral and peripheral states that experience more vulnerability. The exact country assignments and time period reflect one scholarly interpretation and contain more geographic detail than required by the syllabus. Source.

Concentration of Economic Activity

Core-controlled industries tend to cluster in areas that provide access to transportation networks or foreign-controlled extraction zones. This creates uneven development within countries.

Coastal port cities often become enclaves of foreign investment

Interior regions may remain underdeveloped

Local labor benefits only minimally from industrial presence

Limited Industrialization

Because core states dominate advanced manufacturing, periphery states struggle to move into higher-value sectors. Technology transfer is restricted, and local industries may be outcompeted by imports.

Social and Political Implications

Dependency relationships can shape governance structures and social conditions.

Governments may prioritize foreign investors over local needs

Income inequality can widen as elites benefit from external ties

Social services may suffer due to limited public revenue

These outcomes reinforce the cycle of dependency, making it difficult for countries to pursue alternative development paths.

Critiques and Continued Relevance

While influential, dependency theory is not without critiques. Some argue that it underestimates internal factors or the potential for countries to change positions within the global hierarchy. Others note that successful industrializers such as South Korea challenge the theory’s rigidity. Still, dependency theory remains a key tool for understanding contemporary trade relationships, global supply chains, and persistent development gaps.

The theory provides AP Human Geography students with a framework for analyzing why unequal global structures endure and how economic patterns reflect historical and spatial power relations.

FAQ

Dependency theory argues that multinational corporations (MNCs) often reinforce unequal power relations by controlling production, resources, and profits in peripheral countries.

Their activities can restrict local industries through:

Dominance of high-value sectors

Extraction of profits rather than reinvestment

Limited technology transfer

This means that even when MNCs create jobs, they may contribute little to long-term, broad-based development.

The theory focuses on international economic structures because it views underdevelopment as a product of external domination rather than domestic shortcomings.

It argues that:

External control shapes internal policy choices

Trade and financial systems leave little room for independent development paths

Peripheral governments often operate within constraints set by global markets and institutions

Thus, structural conditions are seen as the main barrier to change.

While rare, movement is possible but difficult due to entrenched global inequalities.

Some pathways include:

Strategic state-led industrialisation

Protection of emerging industries

Gradual integration into higher-value production

However, dependency theorists stress that such transitions typically require breaking or modifying dependent relationships rather than relying solely on market forces.

Dependency theory suggests that external economic ties often benefit domestic elites who align with foreign interests.

This can produce:

Concentrated wealth among groups connected to trade, resource extraction, or foreign firms

Limited wage growth for the broader population

Urban–rural divides, as investment is often concentrated in specific export-oriented zones

Internal inequality is therefore viewed as a reflection of external dependency patterns.

The theory favours policies that strengthen domestic economic autonomy and reduce reliance on external actors.

Examples include:

Import substitution industrialisation

State regulation of foreign investment

National control over key industries and resources

These strategies aim to build local capacity and shift a country away from vulnerable, externally driven development paths.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which dependency theory accounts for the continued underdevelopment of peripheral countries.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for identifying a relevant mechanism (e.g., unequal trade, foreign ownership, debt).

1 mark for describing how this mechanism benefits core countries.

1 mark for explaining how this limits economic development in peripheral countries (e.g., reduced capital accumulation, reliance on raw material exports).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Using dependency theory, analyse how historical and contemporary relationships between core and peripheral countries shape global patterns of economic inequality.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for identifying the core–periphery structure central to dependency theory.

1 mark for describing historical roots of dependency (e.g., colonial extraction, imposed economic structures).

1 mark for explaining a contemporary mechanism (e.g., unequal trade, foreign direct investment, debt relationships).

1 mark for showing how these relationships lead to uneven development or limit industrialisation in peripheral regions.

1 mark for linking these processes to observable global spatial patterns (e.g., concentration of advanced industries in the core).

1 mark for overall coherence, clear application of the theory, and accurate geographic reasoning.